Itamar Procaccia, Gregory Falkovich, Victor Steinberg, Norman Zabusky"Everything Flows"Raoul and Graziella de Picciotto, 4th floor

Heraclitus of Ephesus (late sixth — early fifth century BCE) is renowned for his saying, “Everything flows.” In his view, logical inference is inherently flawed because the world is in constant flux, and what is true today may no longer hold tomorrow, as conditions change. While certainly complicating things, this perspective resonates deeply with the challenges physicists face when studying flow processes.

Flow is a universal phenomenon, occurring in gasses and fluids as they move through pipes, across surfaces, or in open space. It is evident in everyday life; for example, when a kitchen tap is turned on, the steady and uniform stream transforms into a turbulent and chaotic flow as the water pressure increases. Another example is the turbulent air vortices forming around and behind a moving car, creating resistance and consuming a significant portion of the energy required for motion. Similarly, reducing turbulence around an airplane’s body could dramatically cut fuel consumption — potentially lowering airfare and making vacations more affordable. Understanding fluid dynamics is also crucial for optimizing the flow of viscous fluids in conduits, such as oil through pipes or blood through our body’s veins and arteries.

Thus, basic research on what was long considered a dead-end question may ultimately lead to more efficient air and land transportation, faster and more cost-effective vehicles, improved industrial systems, and more.

Despite its importance, turbulence remains one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics. We still lack a comprehensive theory that explains the underlying principles governing turbulent flow. In fact, the Clay Mathematics Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has designated this issue — specifically, whether solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations, which describe the motion of viscous fluids, “blow up” or become infinite — as one of the most challenging open questions of the 21st century. A one-million-dollar prize has been offered to anyone who can resolve this fundamental puzzle. The presence of infinite values in the solution would indicate a mathematical model’s failure to accurately represent the physical phenomenon, thus rendering it invalid.

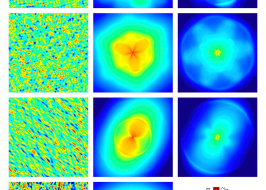

At the Weizmann Institute of Science, Prof. Itamar Procaccia, Prof. Gregory Falkovich, Prof. Victor Steinberg, and Visiting Scientist Prof. Norman Zabusky, investigate turbulence from multiple perspectives. Their research explores phenomena ranging from large-scale atmospheric turbulence spanning thousands of kilometers to the reaction of tiny gas droplets to shock waves.

The images presented in this exhibition, stemming from their research, are neither artistic creations nor didactic exhibits. Rather, they showcase results from studies at the forefront of scientific investigation, revealing the hidden beauty of chaotic flow — a phenomenon that, despite its unpredictability, continues to challenge and inspire.