In Memoriam: Helen Kimmel

A visionary philanthropist through the decades

People behind the science

Helen Kimmel, one of the Weizmann Institute’s biggest donors in its history and an International Board Life Member, died on September 20 at the age of 100. Among her many gifts was her early support for Prof. Ada Yonath on the structure and function of the ribosome, which was instrumental in advancing that line of research which won Prof. Yonath the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009.

Born and raised in New York, where she also raised her family, Helen Kimmel was introduced to the Institute serendipitously, on a flight to Israel with her first husband, Milton Kimmelman, in 1980. Another couple invited the Kimmelmans to the annual meeting of the Board of Governors (precursor to the International Board), and the relationship with Weizmann took root, initially with then-President Prof. Michael Sela and his wife Sara. Her relationship with the Institute spanned six presidents.

Helen studied mathematics at Bryn Mawr College and had a lifelong interest in math and science. Milton was a renowned hotelier and real estate investor, and together they had three children, Abby, Betsy, and Peter. After Milton died in 1984, Helen met her second husband, Martin Kimmel, at a fundraiser she hosted for the Institute in New York. Her philanthropy continued and deepened with Martin.

“Today, the Kimmelman and Kimmel fingerprint on campus is impossible to miss,” says Weizmann Institute President Prof. Alon Chen. “Helen Kimmel touched and influenced so many areas of research over such a long period of time that it is hard to imagine what the Institute would be today without her.”

Helen’s early investment in Prof. Yonath’s work was prompted by Prof. Sela’s suggestion, based on his conviction that research on the crystallization of the ribosome would lead to explosive developments in the coming decades. Helen took a keen interest in Prof. Yonath’s research, and established a professorial chair for her, in 1986; and in Milton’s memory, established the Helen and Milton A. Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure and Assembly which supported Prof. Yonath’s work. Decades later, when Prof. Yonath was awarded the Nobel, Helen and her daughters attended the ceremony in Stockholm.

“I was one of the scientists who benefited from Helen’s analytical and sensible mind,” recalls Prof. Yonath. “Throughout the decades, she showed profound interest in my scientific challenge… She supported my rather unusual efforts when others considered me a dreamer trying to pursue an impossible mission, and as I faced ridicule from colleagues around the world. Helen’s generosity led to a major shift in the nature of my work—initially done in a modest, extremely low-budget lab, but thanks to her, expanded into a highly active research unit. I am grateful to Helen for being a real partner throughout my entire marathon.”

Her giving led to the construction of buildings, a series of research centers, and funds that have advanced research across a wide range of disciplines, including archaeology, stem cells, planetary science, nanoscale materials, magnetic resonance imaging, and more.

Prescient and pioneering

Perhaps her most unique gift came in 1989, together with Martin and under the leadership of then-President Prof. Haim Harari, in which Helen financed the acquisition of 50 acres of land adjacent to the Institute on its east side—increasing the campus area by 20 percent—for potential use in any area the management might see fit in the years to come.

The donation came at a time of major financial instability for the Weizmann Institute, and her wish to fund its purchase of a dusty, remote field—while it was done with the encouragement of Prof. Harari—was met with derision by many, who saw such a move as frivolous, even reckless. “But I believed that we needed to think to the future, and Helen was adamant, and Martin was a real estate businessman who grasped the importance of investing in land,” recalls Prof. Harari. Today, as Rehovot’s population and land prices have skyrocketed, the long-ago purchase is cherished as the Institute charts its path forward.

The establishment of the Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science was also a pioneering step, as it was the Institute’s first foray into applying scientific tools to a field traditionally considered part of the humanities. “It came at a time when we were beginning to witness a new ability for science to penetrate everything,” says Prof. Harari. Another gift, to support the renovation of what became the Helen and Milton A. Kimmelman Building, was also bold in that though it was an old, unattractive structure, Helen saw the need to keep the science moving, and not to hamper research and raise costs unnecessarily by demolishing and rebuilding a more beautiful structure, he adds.

“Helen was not only one of the biggest donors the Institute ever had,” says Prof. Harari, “but also one of the most versatile in terms of the breadth of fields she supported, and it was all done not only with generosity coming from the heart but also with generosity coming from the brain.”

Early in his career, Emeritus Prof. Reshef Tenne of the Department of Molecular Chemistry and Materials Science was the incumbent of a Career Development Chair established by Helen and her first husband, and he headed the Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Nanoscale Science. “I was particularly impressed by their daring decision to reinforce research in our faculty, which was not that popular among philanthropists at that time, because neither did it make any promises to remedy incurable diseases nor did it open new research vistas into the Universe,” says Prof. Tenne.

The Helen and Martin Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation, established in 2007 under the leadership of former President Prof. Daniel Zajfman, is awarded every year at the Annual General Meeting of the International Board to scientists pursuing ‘high-risk, high-gain’ ideas that traditional funding agencies typically don’t consider, and includes funding over five years. “Helen was a unique philanthropist who not only understood, even if only intuitively, the science, but even more so, the scientist,” says Prof. Zajfman. “Her way of thinking was ‘the Weizmann way’: While she always wanted to understand the relevant topics Weizmann scientists were working on, her genuine interest was in identifying outstanding scientists. She knew that great science could only be done by the best minds, and she had a unique flair for recognizing them. This is how the Kimmel Award was born... Helen loved the idea and established a significant endowment fund to support these scientists.”

Helen was first elected to the Board of Governors in 1985, and became a Life Member in 2005. She served as a member of the Executive Council (later the Executive Board) starting in 1988, first as a member and then, as of 2015, an Honorary Permanent Invitee. In 1987, in recognition of her seminal contribution to the prosperity of the Weizmann Institute, the Institute bestowed upon her the degree of PhD honoris causa.

Former International Board Chair Abraham Ben-Naftali had a friendship with Helen Kimmel over 26 years. “She was a genuine partner to the Weizmann Institute who gave smartly by learning and reading about her areas of support before making a decision to move forward, and when she did it made a very large impact. She was also an example and inspired others, and that is no less important.”

—Tamar Morad

Helen Kimmel (L) with Prof. Ada Yonath

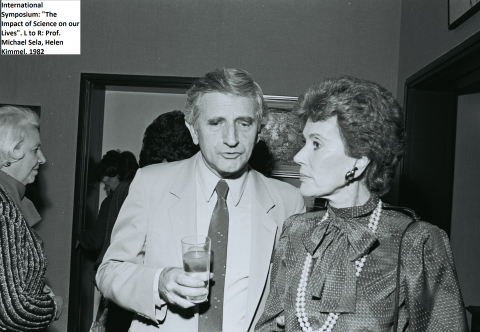

With Institute Prof. Michael Sela

With Institute Prof. Haim Harari (L) and Martin Kimmel (R) at the dedication of the Kimmel Land

With Israeli PM Shimon Peres z"l and Institute Prof. Daniel Zajfman