Agnieszka Kurant, Vardi Bobrow and Yael Balaban"Old, Fake News"David Lopatie International Conference Centre, Weizmann Institute of Science1

In 1996, the physicist Alan Sokal of New York University submitted a paper to Social Text, an academic journal of “postmodern cultural studies” published by Duke University. The title was: Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity. The paper passed the editorial board —and was published. Not long afterward, Sokal announced that the paper been an “experiment.” It was nothing but a meaningless collection of clichés and quotes from post-modernist thinkers, some of whom had published papers in that very journal. Sokal drew a direct line between postmodernism and post-truth, and this set off a flurry of articles, defending and attacking the idea behind the so-called “Sokal hoax,” which is still going today.

Nearly 20 years later, another physicist, David Simmons-Duffin of the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton, initiated another experiment – a quiz for physicists, physics lovers and anyone who loved a challenge. He created a list on which titles of papers on theoretical physics were listed in pairs. One of each pair was a real title take from the arXiv physics preprint server; the other was fake. The fake one – written before the advent of today’s “fake news” – had no paper under it, and some were fairly nonsensical. The participants simply had to identify the real titles.

Some 50,000 rounds of the game were played, and an analysis of the 750,000 answers revealed an average score of 59%. That is, over 40% of the cases, people had identified the fake title as real (and even preferred it over the correct one). That average is close to the results he would have obtained had they simply guessed.

Dominik Stecula, a Polish doctoral student in political science, recently conducted a study at the University of British Columbia to test the awareness and the ability of 700 poly-sci undergraduates to distinguish between real and fake news. He had them assess the home pages of 50 news sites, some generally deemed reliable and others known to disseminate fake news. The students were asked to rate the trustworthiness of each. One of the more startling findings was that half of the students assigned high levels of veracity to two particular fake news sites.

What do the Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity, made-up titles for physics papers, a test of the trust placed in fake news sites, and Robert De Niro’s statement in the movie Wag the Dog (from the book American Hero by Larry Beinhart): “Of course there’s a war. I saw it on TV,” have in common? It is the growing sense that in the second decade of the third millennium, facts have become almost irrelevant. Opinion is everything.

What, in that case, is the point of truth? How can we examine the difference between statements and claims, real and fake news? This, in essence, is the question investigated by Agnieszka Kurant, Vardi Bobrow and Yael Balaban in the exhibit Old Fake News, curated by Yivsam Azgad, , in the David Lopatie International Conference Centre at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Agnieszka Kurant is a Polish-born artist who works in New York. Her investigations of truth and falsehood involve a complex system of economics, culture and society. When she seeks to employ an analytical approach, she “travels back” to a stage in which there are only the basic “elements of the periodic table.” These she examines, one after the other, in an attempt to track the ways in which the changes that may have begun (or are underway) in these elements affect the big picture of the cultural socio-economic and political phenomena we now experience.

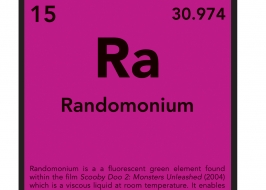

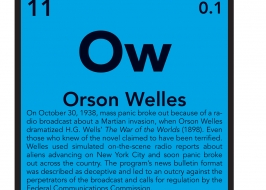

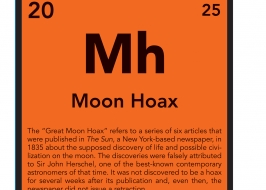

In The Half Life of Facts, she shows us two versions of the periodic table. One is filled with fictional chemical elements; the other presents a table of the “collective delusions and misconceptions,” that inform and shape our lives. In physics, the half-life of an element is an expression of the stability (or instability) of a radioactive isotope. It is the time it takes for half of the atoms in a particular radioactive isotope to change their identities. So in the two tables, Kurant first presents the stories of fictional elements gleaned from books and movies. The second table looks to provide facts and correct common misbeliefs that are passed from generation to generation.

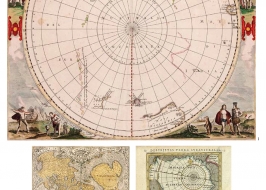

The Maps of Phantom Islands comprises two imaginary maps on which phantom islands appear. Phantom islands are those that people had believed to exist at some point in history. Some phantom islands were products of the Europeans’ limited knowledge of the world and the primitive cartography tools available centuries ago. But there were also islands invented for political and economic gain. The island of Antillia, for example, was the focus of conflict between Spain and Portugal in the 15th century. There is a standard map, a political map of ownership and claims, and a series of individual maps of 30 phantom islands.

Agnieszka Kurant was born and studied in Poland. In 2010, she represented Poland in the Venice Biennale. Her work has been exhibited – among other places – in the Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Tate Modern in London.

True or False?

Yael Balaban, whose installation Ignudi Revisited is in the entrance of the David Lopatie Conference Centre, challenges the concept of reality in her life and her work. She has a BSc in mathematics and an MFA in art. Her work has been exhibited in the Haifa Museum of Art and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (as a recipient of a Minister of Culture and Sport’s Visual Arts Award). Her studio in Haifa is within hearing distance – and sight – it the largest port on this side of the Mediterranean.

In her work, Balaban holds a complex cultural discussion with her artistic heritage. Ingudi Revisited recalls the male nudes (ignudi) painted by Michelangelo on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Balaban painted-sketched them on broken marble slabs. Naturally sketching would precede, chronologically, the act of sculpting; but Balaban reverses the order (and thus reverses time), placing the “original” sketch at the end, as the final product of the creative process. The sketch is done with a rapidograph, and it is filled with spirals and whorls, creating a path that advances and turns back on itself. (Ruth Direktor, curator of contemporary art at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, likens it to such traditional women’s crafts as embroidery and knitting.) The resulting work is a three-dimensional façade made of slabs that are, in essence, flat, two-dimensional planes. Balaban says that the “coils” in her drawings represent the cursive script of the Soviet officer who signed the “rehabilitation document” granted her family to clear the name of her grandfather after he, himself, had been executed for treason under Stalin.

The installation sits within a sandstone niche that is reminiscent of Plato’s cave; the horror that the uneducated have of the rays of enlightenment and knowledge; and the overwhelming tendency of humanity (that is all-too-human, as Nietzsche said in a different context), to shy away from choosing between truth and lie, fact and fake.

Next to this installation, and reflecting the theme of Plato’s cave, is placed (or stretched) another installation: Trap? This work, by Vardi Bobrow, is made entirely of office-supply rubber bands. Connected to one another by flat knots, the work resembles a fantastic, gigantic spider’s web that imparts to the viewer a quiet threat, a presence that requires one to tread softly and wait patiently for the future.

Bobrow lives and works in Tel Aviv. Another rubber-band installation of hers was exhibited in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Her works deal with the concepts of “duration, accumulation and constant transformation.” Indeed, the knots themselves – the very word knot – has numerous connotations. There are the knots tying facts to understanding, messages to belief, knot and ties between people, and even the one that ties space to time.

The implied threat of the spider’s web is completely real. One should not question whether it was made by a giant spider or a person, whether the trap represents a real danger or is “purely” conceptual. In the same way that a psychologist treats a patient for fears that a lion is hiding behind the door without asking if there is really a lion. Bobrow challenges the viewer in her work to accept a constant wavering of one’s world view, oscillating back and forth between the real and threatening, and the fake and manipulative.

Prof. Yadin Dudai, together with Dr. Micah Edelson and other members of his group in the Weizmann Institute of Science, investigates the way in which information is “filed” in our brain and given the “stamp” of fact. This takes place, they found, when the functional connection between different parts of our brain – the amygdala and the hippocampus – is activated. It happens if, when we create a new memory, the source of the new information is construed by our brain to have social and emotional significance. Our “memory files” can then be rewritten, suppressing the original memory. Thus fake news from a trusted source can easily take the place of the memory of true facts.

Peer pressure, in particular, can change the way we remember facts and events. Prof. Dudai and his group asked volunteers a number of true-false questions about events they experienced together, and then informed them that the other volunteers had given an opposite answer to those questions. When tested the next time, many of the participants changed their answers from the correct ones to the wrong ones, and insisted on sticking by those answers in a third test, even after they had been told that their peers’ answers were false. This mechanism, which makes us assign high importance to the opinion of the majority, is probably an evolutionary twist that once helped us survive as a group. Today, however, we are awash in information that is shared by large numbers of other people, often through social media. Among other things, this positive characteristic of attaching importance to “what others say” is easily exploited to spread fake news.

What will be?

Is our ability to discern the fake from the real going to sink into oblivion? Has it already happened? Can we find our way out of the dark Platonic cave, “into the light” of knowing how to tell good from evil? Dr. Sander van der Linden, a neurobiologist from the University of Cambridge, recently suggested that controlled exposure to low amounts of fakery and falsehood can help us develop our critical facilities, thus helping us identify lies when we hear or see them. In a certain sense, he is proposing a psychological “vaccine” which would work like the medical ones that use weakened viruses to prepare our bodies for actual disease. Could this method work? It’s hard to know. Indeed, it is even hard to know if the suggestion was real – or yet another experiment meant to test our ability to reason and remain aware.