Friendly neighborhood fungus outcompetes

Weizmann scientists discover a new species of microbe that may defend against lifethreatening infection

Briefs

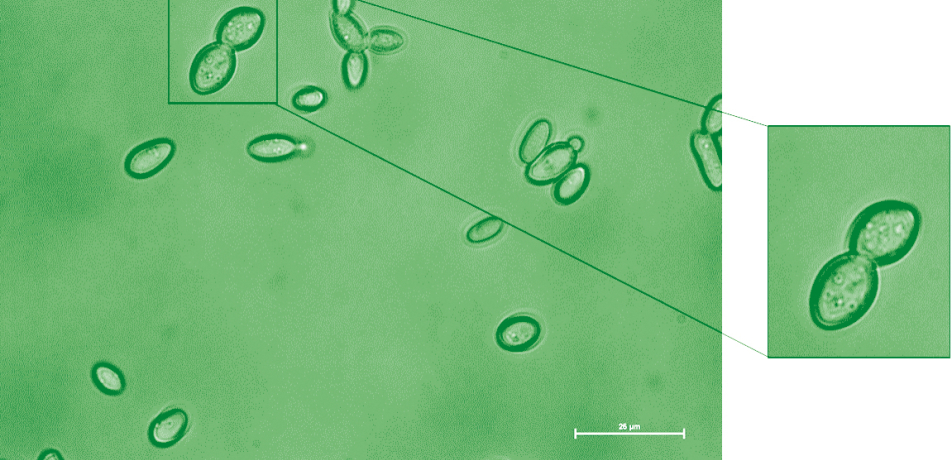

Kazachstania weizmannii, viewed under a microscope. (Image from the Jung lab)

Researchers at the Weizmann Institute, led by Prof. Steffen Jung, have discovered a novel strain of yeast, living quietly in our guts, which may be able to prevent invasive candidiasis, a major cause of death in hospitalized and immunocompromised patients.

Their study, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, shows that this novel species— dubbed Kazachstania weizmannii (in honor of Dr. Chaim Weizmann)—lives harmlessly in the intestines of mice and humans and—as has so far been shown in laboratory animals—can displace the yeast responsible for candidiasis, Candida albicans.

Millions of microbial species live within or on the human body, most of them harmless and many even beneficial to human health. Among these are various species of yeast, which belong to the fungus kingdom. The microscopic yeast C. albicans, commonly found in the intestines and the body’s inner cavities, is usually benign, though occasionally it may overgrow and cause superficial infections commonly known as thrush. Under certain circumstances, however, the yeast may penetrate the intestinal barrier and infect the blood or internal organs. This dangerous condition, known as invasive candidiasis, is commonly seen in healthcare environments, particularly in immunocompromised patients, with mortality rates as high as 25%.

But it turns out the body’s microbiome has an “inside man” who can help.

Like many scientific breakthroughs, this study began with a serendipitous finding. While investigating yeast infections, Prof. Jung and his team in the Department of Immunology and Regenerative Biology noticed that some of their laboratory mice could not be colonized with C. albicans, but rather carried a previously unknown species of yeast.

“Knowing that C. albicans can cause life-threatening disease, we decided to investigate this further,” Prof. Jung says. “And indeed, this line of research paid off: We found that the novel yeast could robustly prevent colonization with C. albicans.”

Working with life sciences colleagues from throughout the Weizmann Institute, they discovered that this species is closely related to yeast associated with sourdough production and appears to live innocuously in the intestines of mice, even when the animals are immunosuppressed.

Most importantly, the researchers found that K. weizmannii could outcompete C. albicans for its place within the gut, reducing the population of C. albicans in mouse intestines. Moreover, although C. albicans can cross the intestinal barrier and spread to other organs in immunosuppressed mice, exposure of such animals to K. weizmannii significantly delayed the onset of invasive candidiasis.

Notably, the researchers also identified K. weizmannii and other, similar species in human gut samples. Their preliminary data suggest that the presence of K. weizmannii was mutually exclusive from the presence of Candida species, suggesting that the two species might also compete with each other in human intestines, although these findings need to be substantiated by further studies.

“By virtue of its ability to successfully compete with C. albicans in the mouse gut, K. weizmannii reduced the presence of C. albicans and mitigated candidiasis development in immunosuppressed animals,” Prof. Jung says. “This competition between Kazachstania and Candida species might possibly have therapeutic value for the management of human diseases caused by C. albicans.”

STEFFEN JUNG IS SUPPORTED BY:

- Sagol Institute for Longevity Research

- Henry H. Drake Professorial Chair of Immunology