Straight answers

Could the origin of scoliosis be in muscle? New research by Prof. Elazar Zelzer

Briefs

While maintaining posture requires the strict positioning and orientation of numerous spinal components, surprisingly little is known about the regulatory mechanism behind these tasks. The failure of this mystery mechanism may result in a common spinal deformity known as scoliosis. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is by far the most common subtype of the disease, appearing without a known cause and in the absence of other skeletal anomalies, and affecting about 3% of school-aged children worldwide.

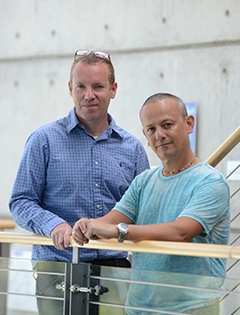

Weizmann Institute molecular geneticist Prof. Elazar Zelzer is deciphering the mechanisms that safeguard the human skeleton from potentially debilitating diseases like scoliosis. He and Dr. Ronen Blecher, an orthopedic surgeon from the Assaf Harofeh Medical Center spine unit, put their heads together to begin tackling this phenomenon several years ago, when Dr. Blecher joined Prof. Zelzer’s lab as a PhD student. Critical to their progress was their interdisciplinary approach—the combination of Dr. Blecher’s specialty in spinal surgery with Prof. Zelzer’s expertise in the genetics of musculoskeletal development.

In their research, the duo determined that scoliosis, which traditionally had been considered skeletal in nature, can be caused by a neurological deficiency affecting muscle function. Their findings, which were published in Developmental Cell in August, shed light on the mystery mechanism that regulates spinal positioning. The insights could lead to new methods for restoring neuromuscular balance in the treatment of skeletal conditions.

It’s a paradigm shift in the thinking about scoliosis, which for a long time was considered a disease of the bone. “The problem is not with the skeleton itself, but rather with the muscle, and not just the muscle, but with something that regulates the tonus of the muscle,” Prof. Zelzer says.

Prof. Zelzer and Dr. Blecher first hypothesized that muscles were involved in the process due to the activity of embedded nerve receptors, called muscle spindles, which are sensitive to the length of muscle fibers and change according to the amount a muscle is stretched. This is part of the human body’s “proprioceptive” circuitry—the system that enables mammals to intuit the location of their extremities.

They generated mutant mice that lacked functional proprioceptive circuitry and, despite the fact that these mice did not have any previous vertebral or muscular abnormalities, they still developed scoliosis at around puberty age.

Specifically, the researchers found that when mutant mice lacked genes that are critical for the formation of proprioceptive receptors, namely Runx3 or Egr3, they developed scoliosis. Moreover, specific inactivation of Runx3 in neuronal tissues induced the same result. These findings suggest that the proprioceptive system plays a key role in spinal alignment.

Now, the scientists are interested in understanding whether the system’s malfunction could be involved in other musculoskeletal pathologies. The key for tackling these complex processes, according to Prof. Zelzer, is their interdisciplinary approach.

“The combination of fundamental biological research with medical knowledge allowed us to come up with this hypothesis and move forward with it,” he says.

That appreciation for such a collaboration led him to hire another orthopedic surgeon in his group: After Dr. Blecher has finished his PhD, Prof. Zelzer recruited Dr. Eran Assaraf, who continues to explore this avenue of research striving to discover new methods to restore skeletons that were damaged by neuromuscular diseases.

Prof. Zelzer is supported by the David and Fela Shapell Family Center for Genetic Disorders, which he heads, the David and Fela Shapell Family Foundation INCPM Fund for Preclinical Studies, Weizmann-University of Manchester Collaborative Projects Program, and the Estate of Bernard Bishin for the WIS-Clalit Program.

Dr. Ronen Blecher (L) and Prof. Eli Zelzer (R)