A century of science and statehood

Dr. Chaim Weizmann’s legacy thrives, 100 years after the Balfour Declaration

Briefs

The Balfour Declaration was signed 100 years ago this week—November 2, 1917—stating British support for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine and ushering in an era of political activity that led to Israel’s founding in 1948.

At that time, Britain’s Jewish community was actively promoting the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, and Dr. Chaim Weizmann was part of that circle of movers and shakers (some of whom, including Israel Sieff and Simon Marks, became future donors to the Weizmann Institute of Science). Dr. Weizmann’s friendship with UK Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour, and with Prime Minister David Lloyd George, with whom he had worked during WWI, was an important factor that contributed to the approval of the declaration.

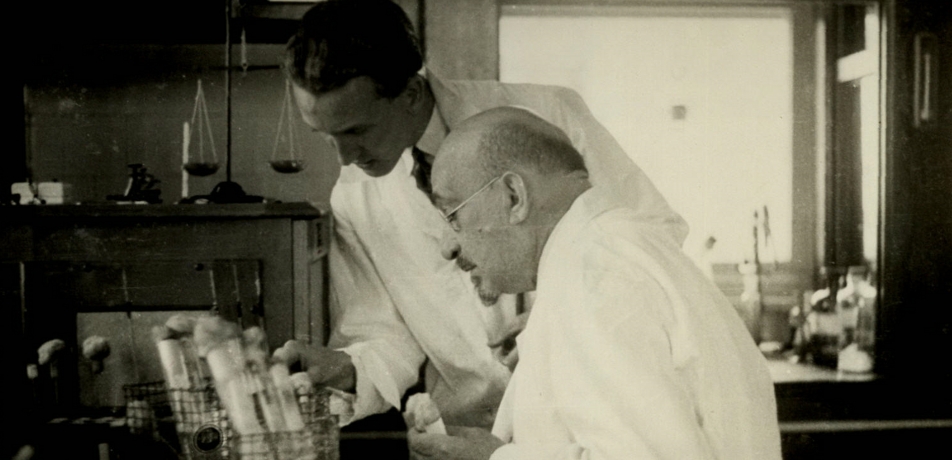

The friendship that developed between Dr. Weizmann and Lord Balfour had its roots in Dr. Weizmann’s invention for the production of acetone by bacterial fermentation of maize starch. Acetone—now commonly known for its use in removing nail polish and as a paint solvent—was of historical importance to the British war effort in WWI because it is a critical ingredient for explosives and munitions.

As a chemist who was committed to advancing basic research, Dr. Weizmann also had his eye on its value for real-world needs. He spent several years developing the basic molecules for the synthesis of rubber, which eventually led to the discovery of a fermentation process for acetone. In 1914, Britain was in desperate need of large amounts of acetone, which was used to pre-treat gunpowder, thereby preventing the abrasion of gun barrels and the release of smoke after firing—which made it difficult for the enemy to identify the location of guns. In those years, acetone was produced in Germany, Russia, and Finland, but because of the war, acetone supplies to Britain were completely stopped. In addition, the existing production method was slow and inefficient, requiring tons of wood that Britain didn’t have.

Dr. Weizmann wrote to the British authorities about his fermentation system; they came to see it, and he demonstrated it to them. Thus the patent was born, and soon after began the production of acetone in industrial quantities. In a gesture of patriotism, Dr. Weizmann declined to receive compensation for the patent until the end of the war, so as not to appear to profit from wartime needs. It was a gesture that reached the ears of Winston Churchill, who had recently stepped down as First Lord of the Admiralty, to be replaced by Lord Balfour. Balfour hired Dr. Weizmann as a paid advisor on the subject of acetone and as an advisor on chemical affairs to David Lloyd George when he was Minister of Munitions.

In 1917, Lloyd George became Prime Minister and Lord Balfour became Minister for Foreign Affairs, and on November 2 of that year, Balfour penned what became known as the Balfour Declaration—a letter to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leader of the UK Jewish community, stating British support for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Dr. Weizmann came to Palestine in 1933 and established the Daniel Sieff Institute for Scientific Research and in 1949 became Israel’s first President. Following his election, the Israeli government named the Daniel Sieff Institute the Weizmann Institute of Science in his honor.

An article in the Israel Chemist and Engineer on the subject summarized the outcome as follows: “…the personal relationships that Weizmann had established with both these leaders [Balfour and Lloyd George] during the years 1915-1917, as well as with many prominent Jewish leaders like Herbert Samuel, who had served as Home Secretary in the Asquith cabinet, Israel Sieff, Simon Marks, Harry Sacher, Julius Simon, Samuel Tolkowsky and others, significantly contributed to advance[ing] the ideas and agendas of the Zionist movement, which culminated in the Balfour Declaration of November 2nd, 1917, which stated: ‘His Majesty’s Government views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.’

This article is based on the article, “Acetone: Science, Business and Politics—100 Years since Dr. Chaim Weizmann’s Acetone Patent,” by Prof. David Mirelman (Weizmann Institute), Prof. Jehuda Reinharz (Brandeis University), Prof. Motti Golani (Tel Aviv University), Prof. Eliyahu Rosenthal (Tel Aviv University), and the Weizmann Archives, Israel Chemist and Engineer, Issue 2, August 2016.