The hidden states of bacteria

Dr. Raya Faigenbaum-Romm is uncovering why identical bacteria behave differently—and why some treatments fail

New scientists

Dr. Raya Faigenbaum-Romm felt the pull of discovery early. “I remember being attracted to science and to making discoveries from a young age,” she recalls. But curiosity alone wasn’t enough. She wanted her work to have an impact on human health. “I became especially interested in translational science,” she says. “I wanted my research to connect to real clinical problems.”

Born in Russia, Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm and her family moved to Israel when she was four. At Shevach‑Moffet, a Tel Aviv high school focusing on science and technology, she studied chemistry and computer science, while taking courses at Tel Aviv University. After high school she served for two years in Israel’s Military Intelligence before completing her undergraduate degree in computer science and chemistry at Tel Aviv University. Later, her graduate work on cancer drug development gave her biological tools and confirmed her interest in biology. But it was during her PhD in Prof. Hanah Margalit’s lab at Hebrew University that Dr. Faigenbaum‑Romm found her calling: bacteria. What captivated her wasn’t simplicity but astonishing hidden complexity.

RNA sleuthing

The challenge was capturing that complexity at scale. Bacteria use small RNAs as molecular switches, binding to messenger RNAs to turn genes on or off as they shift between environments—especially crucial during infection. When Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm began her PhD, only about 150 small RNA-mRNA interactions had been identified, each through individual studies. Drawing on their computational and experimental expertise, Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm and her colleagues developed RIL-seq (RNA interaction by ligation and sequencing), capturing all interactions simultaneously. Applied to Escherichia coli, it revealed 2,800 interactions— expanding the known regulatory network 18-fold. Their study was published in Molecular Cell and in Nature Protocols, and the technique became widely adopted.

The heterogeneity problem

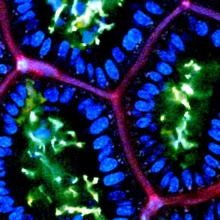

During postdoctoral work with Prof. Nathalie Balaban at Hebrew University’s Racah Institute of Physics, Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm addressed a discrepancy: classical microbiology assumed bacteria from the same patient behaved uniformly, but emerging evidence suggested genetically identical bacteria could exhibit different behaviors—especially in antibiotic resistance. The challenge was identifying these differences and their clinical relevance. Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm and colleagues developed Microcolony-seq, based on a key insight: during active division, bacteria “remember” their behavioral state. The method isolates tiny colonies formed by single bacteria dividing. RNA sequencing of these colonies revealed something remarkable: though the colonies appeared identical, their genes were expressed differently, leading to differences in phenotypic states. Their findings were published in Cell in 2025.

Applying Microcolony-seq to bacteria from a Staphylococcus aureus (staph) bloodstream infection, Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm worked with colleagues at Hebrew University to uncover three distinct subpopulations of bacteria from a single patient, each with different RNA patterns reflecting different virulence levels, highlighting the diversity of bacterial behavior in infections.

“We’ve been treating bacteria in an infection as if they’re all the same,” she notes, “but we observed that they can coexist in different states.” This hidden diversity may explain why treatments fail—antibiotics usually target one subgroup while others evade treatment and survive—and suggests that future precision treatments could be designed to target all subpopulations.

Both sides of the conversation

Drawn to Weizmann’s creative, collaborative, and professional environment, and the ability to turn ideas into experiments, Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm is joining the Institute’s Department of Immunology and Regenerative Biology in the spring of 2026. She plans to use computational and experimental tools in microbiology and immunology to study both sides of the host-pathogen conversation: how immune systems respond to multiple bacterial subpopulations and what mechanisms drive this heterogeneity in the bacteria.

Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm’s collaborative experiences have shaped her vision for her lab culture. “I want to create an environment where group members feel comfortable sharing their ideas, discussing unexpected results, and asking questions,” she shares.

Her work sets a new path forward for the fight against infections: bacteria are not uniform populations but consist of diverse communities that have often been overlooked. Recognizing and addressing this new discovery may ultimately lead to more effective treatments for infectious diseases.

Dr. Faigenbaum-Romm lives with her husband and three children in the central city of Modi’in. In her free time, she enjoys running, reading, and spending time with her family.

EDUCATION AND SELECT AWARDS

• BSc, magna cum laude (2011), MSc (2013), Tel Aviv University

• PhD, Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2020)

• Postdoctoral Fellow, Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University (2020)

• Postdoctoral Fellow, Racah Institute of Physics, Hebrew University (2021-2024)

• EMBO Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (declined due to COVID-19) (2020), Hebrew University Post-Doctoral Scholarship for Excellent Female Students (declined due to COVID-19) (2020), Emily Erskine Endowment Fund Post-Doctoral Researcher Fellow (2021), EMBO Poster Award at The New Microbiology Course (2025)

APPOINTMENTS

• Research Associate, Racah Institute of Physics, Hebrew University (2024-2026)