Prof. Marcus du Sautoy

Q&A

Curiosity may have no boundaries, but will we ever reach a point at which we know everything?

This is a burning question for Prof. Marcus du Sautoy, who explored the answers in his guest talk at the Global Gathering. It is also the topic of his latest book, What We Cannot Know: Explorations at the Edge of Knowledge (2016).

Prof. du Sautoy is a Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford and the Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science, and is a frequent contributor to the BBC and other UK media. In 2009 the Royal Society awarded him the Faraday Prize for excellence in communicating science to the public, and in 2010 he received an OBE from the Queen for his services to science. He is a fellow of the Royal Society. Weizmann Magazine had some questions of its own for the expert science communicator.

Q Why do the unknowns intrigue you?

A The sense of not knowing what’s ahead is what makes life worth living. This is true in science, and in our own lives. It is the unsolved problems that drive science that make it a living, breathing subject. It was the conjectures that I couldn’t solve as a mathematician that first drove me to visit Israel in the search for solutions. I did my postdoctoral research at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I met Alex Lubotzky [former chairman of the Einstein Institute of Mathematics] in 1992. Alex has very different political views than I do; he lives in Efrat on the West Bank; and he’s an Orthodox Jew. I was a left-wing atheist whose only religion was football. But we realized that we spoke the same language. We were able to connect immediately; it was like meeting a long-lost brother. That’s the beautiful thing about maths and science—it’s a language that brings people together.

I fell in love with Israel, traveled everywhere, and gave lectures in many places, including at the Weizmann Institute. And I met my wife, Shani, who was studying at Bezalel. I came back to the UK with a theorem and a wife.

In science, we have turned over so many stones, illuminating so many unexpected things. But that has made me think: Is there a limit to what we can know? I am a product of the Oxford system, where you spend a lot of time with people outside your discipline, to be broad-minded. This is how I learned about the theologian Herbert McCabe, who declared that ‘to assert the existence of God is to claim that there is an unanswered question about the universe.’ And this brought me to the question at the heart of my new book: ‘Can we identify things that will always remain beyond knowledge?’

Q Mathematicians don’t typically spend their time communicating

science to the masses. Why do you do it?

A My initial career trajectory was a pure scientific one, but the climate in science has changed. There is an awareness that science is having a massive impact on society and we are going to need to understand science in order to make major decisions about directions in which society should go. Take stem cells: If you don’t understand what a stem cell is, you are disenfranchised from any debate about their use. So, especially in the UK, there is a realization that it is the responsibility for scientists not just to make the big discoveries but also to communicate to the public what they’ve discovered.

In 1995 I received a 10-year research fellowship from the Royal Society to continue the research I had started as a postdoc in Israel. Since I didn’t have any teaching duties it gave me the space also to explore communicating some of the breakthroughs that were happening in my area of mathematics to a wider audience. Knowledge doesn’t exist if it’s just in your own head. It has to exist in other people’s heads. The Royal Society was very supportive of these efforts to communicate science to the public especially because there was a recognition that science was having an ever bigger impact on society.

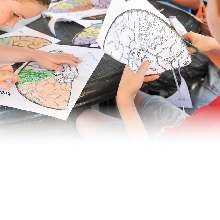

The communication work I did culminated in 2008 in my appointment to the Simonyi professorship, which had been established by Charles Simonyi [who built Microsoft's profitable products Microsoft Word and Excel]. Oxford was very farsighted by creating a named professorship that carves out time and funds for scientists to communicate science to the public. I make TV and radio programs, write books, speak everywhere I can, and I have trained a small army of Oxford students to go out to schools and talk about the value of science and maths.

We are trying to fight the ease with which people say they are bad at math and wear it as a badge of honor. The prevailing approach in education has been that there is science and there is humanities—never the twain shall meet. I’m working to make sure people see the two as fully integrated.

Q What does the public need to understand most?

A The impact of machine learning on society. Are you going to trust an algorithm to manage your health? It’s ultimately going to be better than your doctor, but people’s first reaction will probably be negative. So people need to understand what algorithms are and why they matter.

Even between scientists, communication must improve. It’s hard for a biologist to talk to a mathematician, a physicist to a chemist: It is as if they are from foreign countries. There are many areas in which there is crossover, and that’s where all the exciting stuff is happening. I know this is happening at Weizmann. But science remains like a foreign country for many people. So I see my role as an ambassador for the ‘superpower of science’.

Q Why do you love math and science?

A Scientists are driven by the basic desire to know. It is a basic human trait. Just by understanding, we can change the universe, for good. The Weizmann knows this, and does it extremely well; that is why, when I learned about the Weizmann Institute’s Science on Tap [science talks at pubs] I got involved in a similar series here in the UK. We call it A Pint of Science. And the Global Gathering is also a great platform to tell many good stories about science. For me one of the most exciting things about being a scientist is being part of a good story that goes back to Galileo and Newton. Each new generation is taking the baton and running with it. It is a wonderful time to be a scientist. It feels like a new Newtonian age.

Prof. du Sautoy is the also the author of The Music of the Primes: Why an Unsolved Problem in Mathematics Matters; Finding Moonshine: A Mathematician’s Journey Through Symmetry; and The Number Mysteries: A Mathematical Odyssey through Everyday Life.