By exploring the relationship between molecules and the crystals they form, two Weizmann scientists helped modern chemistry take shape

When taking stock of the breadth of scientific discovery in the last century, one of the most seminal insights was that biological activity at the micro level is integrally related to and, in great part, determined by the physical shape and structure of biological material.

A key contributor to this realization was the development of X-ray crystallography, an analytical technique based on X-rays that is used to figure out the atomic and molecular structure of materials in their solid, crystalline state. The structures of penicillin, insulin, vitamin B12, proteins, ribosomes, and—most famous of all—the DNA helix, were determined by this technique. In fact, crystallography was the main tool used by 29 Nobel laureates throughout history, including Weizmann’s own Institute Prof. Ada Yonath.

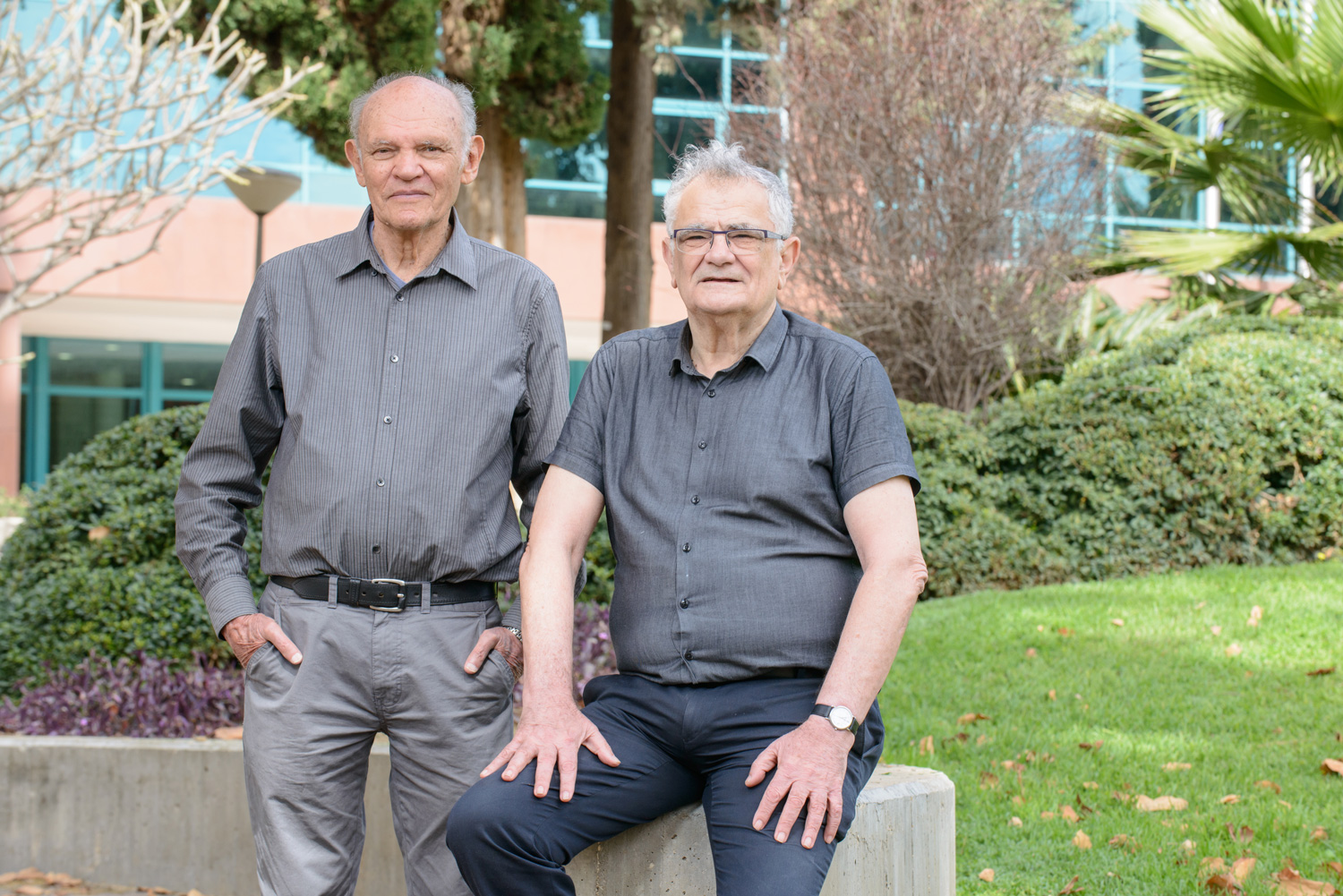

Two Weizmann Institute chemists, Emeriti Professors Meir Lahav and Leslie Leiserowitz of the Department of Molecular Chemistry and Materials Science, have been at the beating heart of the field of molecular chemistry and X-ray crystallography. They have received worldwide renown for a cascade of discoveries that have expanded and enriched the field. In a scientific partnership that lasted decades, they fused Leiserowitz’s expertise in X-ray crystallography with Lahav’s expertise in organic chemistry. In doing so, they literally and figuratively filled out new dimensions in science.

Crystal formation is one of the most fundamental phenomena in chemistry. The structure of organic crystals is of particular importance because the crystal shape reflects the 3D structure at the molecular level. Together, they have revealed the reciprocal influences of three-dimensional molecular structure upon structures of organic crystals—meaning, how molecules assemble into crystals, dictating the morphology, or shape, of crystals; and how molecules control he physical and chemical properties of crystals.

Their expertise has been recognized with a series of highly prestigious, including the Wolf Prize, in 2021; the EMET Prize for Art, Science and Culture (EMN Foundation) in 2018, and the Israel Prize, the State of Israel’s highest honor in 2016. Both are elected members of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina.

“They linked the microscopic world with the macroscopic world,” says Prof. Milko van der Boom, former head of their department and Dean of the Faculty of Chemistry. “Their findings are staggering and the implications are manifold, from drugs to malaria treatment to cloud seeding. The seminal work by Meir and Leslie can be considered a dream realized. By working closely together and combining their creativity and expertise, they taught us a lot about the power of human potential and how to harvest it.”

In creating methods to define and control the architecture of crystals using tailor-made additives, their insights contributed to a growing body of evidence that sorting out molecular chirality—the mirror-image nature of many molecules—has real implications for human health. The pharmaceutical industry, for instance, relies on a refined understanding of molecular structure both in order define and synthesize drugs and also in order to ensure drug safety.

In doing so, they closed a loop that first opened with none other than the French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur in the mid-19th century.

When the lab is a vineyard

Pasteur, who was most well known as the father of germ theory, also made groundbreaking findings in chemistry.

Among them was his discovery that the molecules of the living world are chiral—from the Greek word ‘cheir,’ meaning hand—meaning that they have a pattern or structure cannot be superimposed, like our hands. And he saw that they have a have a single handedness, as if they were only one side of a mirror image, also known as homochiral. Thinking of it in full human body terms, it would be as if we always possessed a right hand and never a left one.

His epiphany was that inorganic, synthetic compounds are chiral but have dual handedness, or, in other words, are heterochiral, whereas biogenic organic compounds—those brought about by living organisms—possess chirality but only single-handedness.

How did he do it? The lucrative wine industry in France had a partner in Pasteur, often enlisting him to diagnose and advise when something went awry in the fermentation process. One day, in examining the residue in a vat of wine gone bad, he crystallized the wine’s tartaric acid, as well as a tartaric acid that he synthesized in his lab. When he dissolved the natural (biogenic) crystals in solution, the solution was optically active—meaning, light rotated through it. When he dissolved the synthetic acid, it was not optically active. He then separated the right-and left-handed forms of the synthetic crystals, and saw that each, separately on dissolution, rotated light in opposite directions. He thus deduced that biogenic crystals only had single handedness.

His finding effectively established the field of stereochemistry—the arrangement of atoms into molecules and the arrangement of such molecules into their solid states. While scientists understood the value of his discovery and continued that line of investigation, it became real to the public in the 1960s with the drug thalidomide, prescribed to pregnant women for the treatment of morning sickness, after it caused severe birth defects in thousands of children. In trying to unravel the drug’s defect, it was found that while the left-handed thalidomide, known as an enantiomer, was safe and effective in treating nausea, the right-handed enantiomer one was highly toxic.

Because of this case and others, in 1992 the Food and Drug Administration outlined guidelines on chiral molecules in drug development.

The questions that arose from the Pasteur discovery of chirality continued to perplex and intrigue subsequent generations of scientists: How do molecules organize themselves into crystals? What determines the structure of crystals? Why do the molecules of the biological world have only a single chirality? How did chirality in the organic world arise from the non-chirality of the inorganic world?

Organic symmetry

After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, another German physicist, Max von Laue, came up with the idea that crystals would behave like a 3D grating and diffract the X-rays with their electromagnetic radiation, and under the condition that the distances between the atoms in the crystal were of the same order of magnitude as the X-ray wavelength. He tried this on of zinc sulfide crystals. It worked, and the method was born.

X-ray diffraction creates a picture scattered with spots—data that allow scientists to determine the way in which atoms are arranged within a given molecule. Laue’s discovery, which became known as X-ray crystallography, led to work by Sir William Henry Bragg and his son Lawrence, who laid out many of the basic methods for determining structures of crystals, starting with zinc sulfide and sodium chloride, otherwise known as salt.

Many molecules of the natural world arrange themselves into crystalline structures on their own. For instance, crystals are ubiquitous in the human body and help it properly function in a myriad of ways—or underlie malfunction. Gout, for instance, occurs when urate crystals, created by a buildup of uric acid, accumulate in the joints, causing inflammation and pain. In the animal world, fish, chameleons, and many insects use organic crystals for specific functions such as vision, camouflage, and thermal regulation. Crystals also exist in in the inorganic world in metals, minerals, salts, and ice.

In other cases, molecules must be induced into a crystalline state in order to assemble their components and structure, and X-ray crystallography is one of a number of tools used to determine the molecular architecture of the crystal. When penicillin was discovered almost serendipitously by Alexander Fleming, for instance, the next step was to determine its structure by X-ray crystallography in order to duplicate and synthesize the first antibiotic for mass use. This played out in the US and UK during World War II—a breakthrough that resulted in the Nobel Prize for the British X-ray crystallographer Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin.

One of Hodgkin’s peers was Rosalind Franklin, who, using the technique, discovered the helical shape of DNA, which played a key role in the discovery of DNA, famously attributed to Francis Crick and James Watson.

One of Hodgkin’s students was Prof. Gerhard M. J. Schmidt, who fled Germany before the war and set up one of Israel’s first X-ray crystallography labs at the Weizmann Institute in the early 1950s. It was in the Schmidt lab that Lahav and Leiserowitz met, as PhD students. The lab was focused on various topics, including solid-state photochemistry—the chemical effects of light—crystal engineering, the determination of electron density of molecules in crystals, and protein crystallography. Having completed his own studies in organic chemistry with another Nobel Laureate, Sir Robert Robinson, Schmidt focused his research on combining chemistry and crystallography.

Their mentor also provided them with a strong philosophical foundation about approaching their research. “Because we didn’t have big labs, we had to find a way to benefit from each others’ knowledge and expertise,” says Lahav. “And so, Institute labs began this synergism organically, interacting with one another and with labs overseas. Schmidt saw that this necessity for interdisciplinary work would transform into a hallmark of Weizmann research and enable the Institute to lead the way in many fields.”

“He also used to say that Israel was a small country and so its people didn’t have the same resources as our colleagues in other places like the U.S. and Europe,” recalls Lahav. “And so in order to compete with large and sophisticated lab groups, we had to focus on very specific, unique questions that aren’t the central focus of scientific activity in the world, with the hope and expectation that one day these unique questions will become the leading questions in the field.”

The nexus of molecular chemistry and X-ray crystallography was one such unique area of exploration.

Building bonds

Meir Lahav was born in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1936. When the Soviets halted the deportation of Sofia’s Jews to Nazi concentration camps in 1944, he and his family were among the 48,000 Bulgarian Jews whose lives were spared. In 1948 his family immigrated to Israel, and settled in Kfar Ata (later Kiryat Ata), a suburb of Haifa. He began learning Hebrew at age 12, and English at age 15. “I had to put French and Bulgarian behind me and begin learning two new languages,” he recalls.

He attended high school in nearby Kiryat Haim, where his chemistry teacher, a man named Gedalyahu Marmur, sparked his interest in the field with his unique approach of giving his students a small taste of a subject and then sending them off to the library for “fishing expeditions” in which they were to follow their curiosity.

“After graduating from high school, I knew I would spend the rest of my life dedicated to chemistry,” he recalls.

He served in the Golani Brigade in the IDF, and entered the Hebrew University where he obtained a combined bachelor’s and master’s degree in polymer chemistry in 1962. He then became intrigued by the fact that molecules in their solid state—crystals—can undergo reactions, and those reactions could be monitored by applying X-ray diffraction techniques. That’s when he decided to pursue his PhD in at the Weizmann Institute, and “that’s the point at which I fell in love with the chemistry of crystals,” he says.

His doctoral thesis was in the field of topochemistry—the understanding of how the arrangement of molecules within crystals dictates the structure of the resulting molecules.

He attained his PhD in 1967, and stayed for two more years before going to Harvard University for a postdoctoral fellowship with Paul Doughty Bartlett, where he investigated the properties of explosive materials, an unrelated avenue.

Leslie Leiserowitz was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1934. His parents were immigrants from Latvia and Lithuania; his mother left in the wake of the Russian Civil War in 1921 and his father in the early 1930s. His mother was a dressmaker. “The sewing room in our house in ‘Jo-berg’ was always full of fabrics with a variety of patterns. In retrospect, I think one of the reasons I was inclined toward my fascination with crystals was because I grew up with patterns all around me,” he says.

He studied electrical engineering as an undergraduate at the University of Cape Town. Upon graduation, and having not found inspiration in his engineering jobs, he filled his days hiking up nearby Table Mountain and on sandy beaches, looking for gainful employment, and reading whatever he could about science. He read the seminal book on X-ray crystallography, The Crystalline State, by the father-son pair William Bragg and Lawrence Bragg, and The Optical Principles of the Diffraction of X-Rays, written by one of his undergraduate professors, Reginald James. (James, interestingly, had been a member of Earnest Shackelton’s failed Endurance expedition to Antarctica). Another book, The Soul of the White Ant, by Eugene Marais, about the social organization of ants, was eye opening. “In later years, I realized that ants were like molecules coming together into crystals, and in keeping with the concept: local interactions lead to global order,” he recalls.

His passion had begun to, well, crystallize.

He returned to the University of Cape Town (UCT) to pursue a master’s degree in physics, and upon graduating, he began reading papers on crystals by Schmidt at the Weizmann Institute. He applied to the lab for his PhD and was accepted. Leiserowitz wasted no time, and departed by ship for the UK and, from there, hitchhiked across Europe to Italy, and from there boarded a ship to Haifa.

“The story goes that a member of the physics faculty at UCT convinced Schmidt to change his mind about me,” says Leiserowitz. “But it was too late—I was already en route and was unreachable. Five years later, Schmidt told me that when I arrived, he didn’t have the heart to let me down.”

In Schmidt, Lahav and Leiserowitz found an advisor “who was interested in a great many things—his mind was like an interdisciplinary lab itself,” Leiserowitz recalls. In setting foot in the chemistry labs on campus, they found a beehive of activity where a multitude of languages were being spoken. They befriended scientists from Rhodesia, Holland, the U.S., Hungary, Poland, France and Romania. The mixture of cultures and perspectives created a vibrant research and human ecosystem where everyone was learning from each other—words, techniques, knowledge.

The central aim of Leiserowitz’s PhD studies was to understand the behavior of thermochromic crystals, which change color with temperature. Another study, which Leiserowitz initiated on his own, involved mitigating the high absorption of X-rays in crystals. The resulting publication was extensively cited, and, in later years, it proved to be a key step necessary in working out the morphology of a crystal.

After Leiserowitz attained his doctorate in X-ray crystallography, Schmidt asked him to do a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Heidelberg and help set up an X-ray crystallography lab there at the Institute of Chemistry in the group of Heinz A. Staab. The initiative was part of Schmidt and Staab’s efforts to establish scientific ties between Israel and Germany—an effort that eventually led to the establishment of formal diplomatic relations between Israel and Germany.

“Initially I didn’t love the idea of going to Germany. My family in Lithuania had lost their lives because of Nazi Germany,” he says. But it was a short assignment—just 18 months—and he agreed. It proved fruitful and interesting. After helping to establish the lab, which also involved determination of a complex organic crystal structure by direct methods (for which Leiserowitz spent months writing the code), he recalls, “I would walk along the ‘Philosophers way’ or the Neckar River with my two eldest daughters, aged 3 and 4, to give my wife Ruchama a break, since she was at home with the baby, and think about what I would do when I came back to Weizmann.” Like his nature walks in Cape Town that led him to a career in science, his river walks helped him focus on planning his research agenda.

Upon returning to the Institute in early 1968, he initiated a study about how to recognize weak hydrogen bonds, at a time when the phenomenon was regarded with skepticism. He also engineered so-called “co-crystals,” composed of two different hydrogen bonding groups. Three years later, Schmidt died, and that same year, Lahav returned from his postdoc at Harvard. Seeking like-minded partners, the two former students turned to each other. When they began trading ideas, says Lahav, “The chemist had to learn a bit about crystallography, and the crystallographer had to learn a bit about chemistry, and in this way our collaboration grew.”

A ‘gold mine’

Finding fertile ground in the meeting point of their areas of expertise, they advanced their joint research and it grew in intensity, with each scientist complementing the other in a symmetry not unlike the mirror images they were uncovering in their labs. It was the beginning of a scientific partnership that would last decades and generate prolific results.

They laid key groundwork in the 1970s, and then, starting in the early 1980s, their discoveries began coming in quick succession.

Taken together, the work of Lahav and Leiserowitz established a bridge between crystal structure, crystal morphology, and molecular chirality. They found ways to control crystallization and grow crystals with a predicted structure and morphology using tailor-made additives; until that time, the design of crystals was done by trial and error. That enabled them to establish the so-called “absolute configuration” of chiral organic molecules from their crystal morphology, which enables scientists to determine the handedness of a given molecule.

In the course of their investigations, they become interested in the role played by structures crystalline clusters created at interface between air and water. This body of work eventually led them to engineer crystalline thin films floating on the water surface that induced crystallization of crystals of unique shapes. This necessitated their elaboration of new crystallographic methods to determine the structures of those films. These crystalline thin films were characterized by X-ray diffraction methods, in collaboration with the Danish physicists Jens Als-Nielsen and Kristian Kjaer at the X-ray synchrotron light source Hasylab in Hamburg. This collaboration began in 1986 and lasted for nearly two decades, spurring a myriad of results.

And they made another important finding: that the symmetry of mixed crystals (those with at least two chemical elements) is reduced in comparison to the host crystals. As a result, the mixed crystals unveil new physical properties, such as pyroelectricity when exposed to a thermal fluctuation or when compressed.

Like expert Lego-builders, Lahav and Leiserowitz found creative ways to assemble and disassemble structures and see how the results played out in terms of the crystals’ activity and function.

“I guess because I’m from Johannesburg, which was a gold-mining town, I kept on thinking of what we were doing as a gold mine,” says Leiserowitz. “Every week we were finding nuggets of gold.”

They never argued about—or even discussed—who would get more credit than the other. “It always just kind of worked itself out,” says Leiserowitz. “But we always argued about science—in fact, for 15 years we argued about the nucleation process of ice, and we still don’t agree.”

Lahav recalls taking a car ride with the Nobel laureate in chemistry Vladimir Prelog (1906-1998), from ETH in Zurich, who was taken aback by all their disagreements, and marveled at their ability to work together. But it was precisely the open dialogue—that ability to hold each other in check with no egos—that made it so fruitful, they say. Says Leiserowitz, “Only afterwards, after all those years of collaborating, did we realize what an unusual and unique partnership we had.”

Human catalysts

The pair jointly mentored dozens of students, and in the process created a cadre of chemists who would take their insights to new directions.

Dr. Isabelle Weissbuch, a former PhD student, became a staff scientist in the Lahav lab and collaborated with Lahav and Leiserowitz on most of their projects over several decades.

Emeritus Prof. Lia Adaddi came to the Lahav lab in the 1970s as a young immigrant from Italy to pursue her PhD, and continued to collaborate with them on and off throughout the years. Today, Addadi and Leiserowitz are advancing research on atherosclerosis, the buildup of cholesterol in the arteries, which involves crystal formation. A member of the Department of Chemical and Structural Biology, Addadi says, “I believe that their body of work was an amazing and unique achievement, and I consider myself very lucky to have been at the time part of the team. These were exciting times, which not only significantly contributed to shaping my future, but also, and more importantly, shaped the future of stereochemistry and of solid-state organic chemistry.”

The Addadi lab went on to focus on how crystals interact with their biological environment and serve a physiological function in the body—in health and disease—both at the molecular level and the cell and tissue level. “We analyzed, invented, and discovered together, and what that knowledge generated then continues with me in so much of my work today,” she says.

Dr. Linda Shimon, a Senior Research Fellow who heads the X-ray Crystallography Lab in the Department of Chemical Research Support, did her PhD in the Leiserowitz lab. Today, she says, the technology and knowhow accumulated in the field throughout the years allows her to characterize a crystal that once took eight or nine months to define decades ago, to do now “in a matter of hours… and Leslie helped us get to the point we are today.”

Another former Leiserowitz student, Dr. Sharon Wolf, is today a Senior Research Fellow, and headed the Electron Microscopy (EM) Unit until 2021. EM uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination to obtain high-resolution 3D images of biological and non-biological specimens including tissues, cells, organelles, and macromolecular complexes. Upon arriving at Weizmann in the early 1990s, she says, “I was absolutely mesmerized with Leslie’s lectures of crystallography—the elegance of it,” she says. “I cannot overstate how significant it was for me to have been part of the research that Leslie and Meir did together. In my first two years of my PhD, we had one paper each in Science and Nature, which were highly cited. They were a genius combination... Leslie formed my worldview about scientific research, which was what I’d call ‘ego-less science’: to be open-minded to new possibilities you might never have considered in an overall quest to understand how nature works.”

Malaria and more

Lahav also went on various leadership roles at the Institute, including Vice Chairman of the Scientific Council and head of the Department of Materials and Interfaces (the precursor to the current department). He had a decade-long consulting relationship with DuPont, one of the world’s largest chemical companies, helping it ensure the purity of chemicals and avoid unwanted byproducts. For nearly 15 years, Leiserowitz was a consultant for various companies in the Boston-Cambridge area, including TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, and Moderna.

Among other studies, the collaborators found how the buildup of wax crystals in fuel at cold temperatures—think about the difficulty of starting a car in the dead of winter—could be prevented with designing better fuel additives.

When they became emeritus (Leiserowitz in 2002 and Lahav in 2004) they both turned to new collaborations with younger scientists. They continue to advance a pursuit begun in their active research years: finding ways to manipulate the creation of ice—the crystallization of water—which, they hope, may lead to new ways to make ice at different temperatures and thus provide alternative methods of cloud seeding. Cloud seeding is a method for generating or moderating precipitation, which could prove critical for a warming planet.

After his retirement, Lahav has continued to exploit the unique properties of the reduction of the mixed crystals, in collaboration with Prof. Igor Lubormirsky and Dr. David Ehre. They demonstrated that the freezing of super-cooled water by electric field is a chemical process triggered by different ions. They used those crystals for the understanding the macroscopic effects of the charging of crystals by cooling or heating, called pyroelectricity, or by the applying of pressure—called piezoelectricity—on the molecular level. Through the use of synchrotron facilities in Europe (which offer electromagnetic radiation to characterize a range of materials) they created new methods for examining and characterizing molecules at this interface, which has various applications.

And then there’s malaria. About 20 years ago, one of Leiserowitz and Lahav’s students, Ronit Buller, came across a short article in Nature describing the structure of the submicron-sized crystals of the malaria pigment. The article suggested that the most commonly prescribed drug for treatment of the disease, quinine, interferes with the nucleation (instigation) and growth of the malaria pigment inside infected red blood cells. Recalling how his father, who had spent years in central Africa, described the devastation it caused to local populations, Leiserowitz says “it was a revelation to learn that malaria is a form of pathological crystallization.”

He picked up on his student’s efforts and has been advancing it ever since. He is doing this through a collaboration with Sergey Kapishnikov, Jens Als Nielsen, and Prof. Michael Elbaum, a member of the Department of Chemical and Biological Physics and an expert in imaging at the nanoscale level.

“The malaria pigment crystal is the Achilles’ heel of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum,” says Leiserowitz.

In malaria, the mosquito-borne parasite that causes the disease consumes the contents of human red blood cells, in a compartment called the food vacuole, breaking down hemoglobin into peptides and heme, a molecule that is toxic to the parasite. To prevent death, the parasite sequesters the heme into hematin crystals. Quinoline-type drugs like quinine act by smothering the hematin crystals, binding to non-crystallized hematin, which then clog up the membrane-forming the food vacuole, resulting in the parasite’s death.

Looking in the mirror: Reflecting on lives spent in science

From the Faculty of Chemistry’s earliest days, its labs were an interconnected web of ideas—a mid-century equivalent of a start-up incubator from which eventually emerged a broad spectrum of sub-disciplines, from organic chemistry to biophysics, structural biology, Earth and planetary sciences, materials sciences, quantum optics, magnetic resonance and more. This web, says Lahav, was best possible breeding ground for outside-the-box research.

So was their lab’s first physical home. The Ziskind Building housed some of the Institute’s most preeminent scientists in those years, including Prof. Mendel Cohen—an expert in photochemistry, or the effects of light like ultraviolet, on chemicals and Prof. Fred Hirshfeld, a physicist from the U.S. with a strong bent toward mathematics and physics who developed mathematically based methods for extracting data on electron density from X-ray diffraction.

Lahav’s career at Weizmann also has included family: His late wife, Yona, who was a teacher at the De Shalit high school and taught Hebrew to new immigrants in the faculty and throughout the Institute. His daughter Dr. Michal Lahav went on to become a chemist and is now a senior staff scientist working with Prof. van der Boom. She is also studying the relationships between molecular structures and materials: crystals and thin films.

At its core, their joint research was based purely on curiosity. “If we look at the history of science, and the outcomes that we benefit from today, they all began with a deep curiosity, without any kind of sense of where it was going to go,” says Lahav. “And if you think about our work, no one, including us, would have considered the potential application. It is only once you are deep within the exploration and understand all the many related aspects that you even have the possibility of considering how what you’ve done might benefit humanity.”

Donor support

Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto

Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory and

Head of the Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science

Dangoor Chair of Archaeological Sciences

Prof. Michael Elbaum

Knell Family Institute of Artificial Intelligence

Fritz Haber Center for Physical Chemistry

Sam and Ayala Zacks Professorial Chair