In all their diverse and plentiful career and voluntary pursuits, Harvey and Dr. Ellen Knell are builders—of homes, educational opportunities, and of the arts, music, science, and medicine, and of community and family.

Most recently, they have made one more creation: The Knell Family Institute for Artificial Intelligence, which will advance AI research across the natural and exact sciences at the Weizmann Institute. The Knell Institute will be housed in new state-of-the-art building, the Ilana and Pascal Mantoux Building for Artificial Intelligence, which will serve as a hub for AI experts who will work hand-in-hand with Institute scientists on a range of research questions, and for computer scientists who will be developing new tools for new AI methods. It will also be home to the Information Technology Division.

The new Knell Family Gate will be nearby the new building and will serve as a key entry and exit point for scientists and staff across campus.

The timing of the Knells’ decision to make this gift holds additional meaning beyond the donation itself, Weizmann President Prof. Alon Chen noted at the dedication ceremony on campus at the Annual General Meeting of the International Board in November 2024. The gift “comes in the midst of Israel’s most difficult year—a year in which the whole country is simultaneously grieving and fighting an existential war. What Ellen and Harvey and their family have done isn’t just a statement about their support of Weizmann, but of statement about their solidarity with Israel, and an investment in the future of the country. Ellen, Harvey, and their children and grandchildren, deserve our great gratitude for this truly visionary gift.”

The Knells have a long history with the Weizmann Institute marked by leadership and generous philanthropy.

Both are members of Weizmann’s International Board and Harvey is National Chair of the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science. Harvey is a co-chair of the new Empower Tomorrow campaign, which aims to raise ambitious sums from philanthropic partners for the Weizmann Institute over a decade (2020-2030). Harvey also chaired ACWIS’ 75th Anniversary Campaign, and the couple has nurtured and expanded the American Committee’s circle of supporters. They both received honorary doctorates at the 74th Annual General Meeting of the International Board in 2022, in recognition of their outstanding lifetime achievements, dedication to scientific research, and decades-long friendship with the Weizmann Institute.

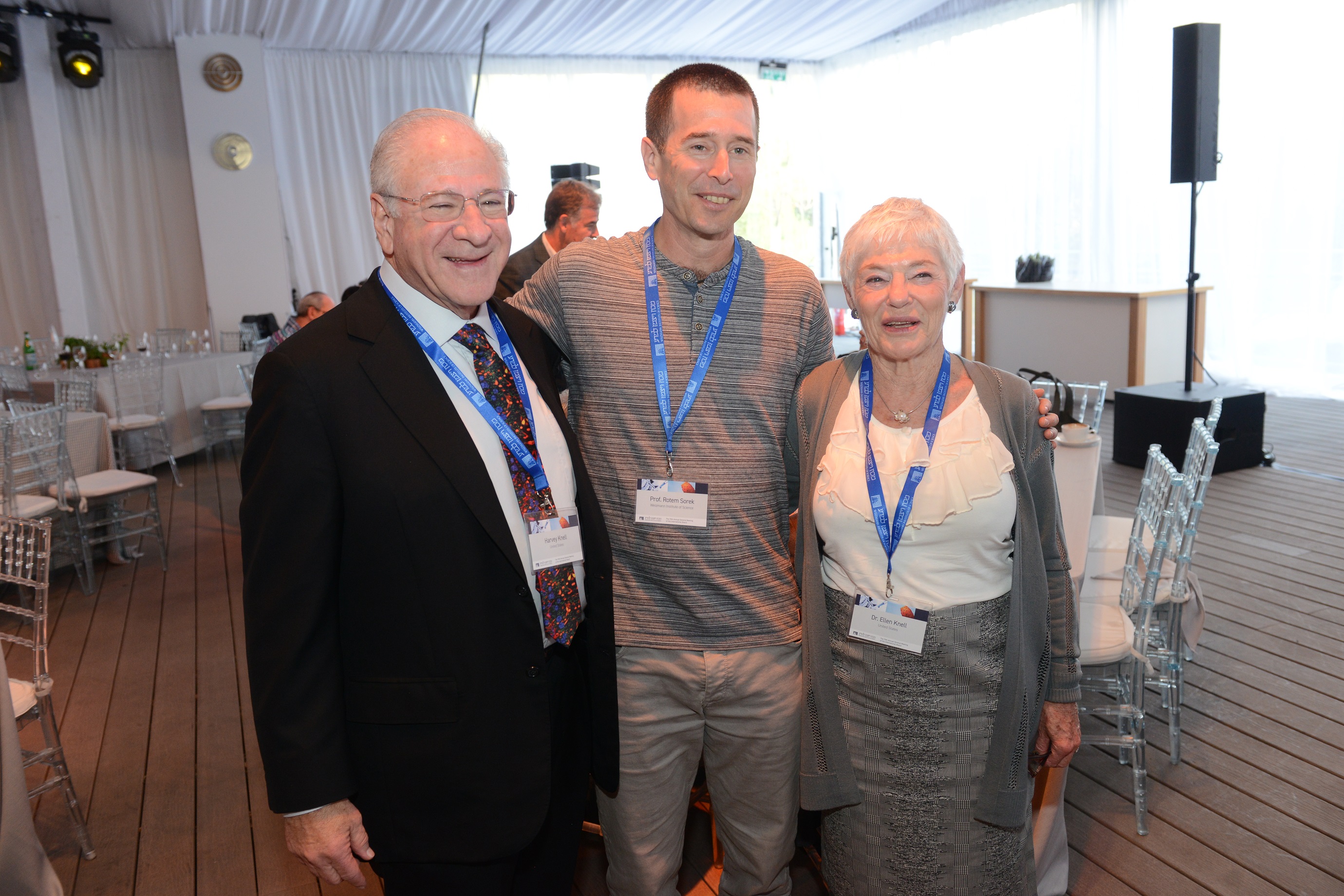

Longtime supporters of the Weizmann Institute whose relationship with the Institute dates back decades, the Knells are also part of the prestigious President’s Circle comprised of the Institute’s most generous donors. Among their major gifts is their establishment of the Knell Family Professorial Chair, whose current incumbent is Prof. Yardena Samuels of the Department of Molecular Cell Biology, and the Knell Family Center for Microbiology, headed by Prof. Rotem Sorek of the Department of Molecular Genetics.

Tapping into American trends

Born in Youngstown, Ohio, Harvey moved with his parents and siblings as an infant to Southern California. In 1946, his parents purchased a business in Rosemead, California, with a sign on the building that read: “Ole’s House of Bargains: We Buy and Sell Anything that Does not Eat.”

Harvey recalls his father telling the story of his first two customers. One came to the store with a trunk load of broken glass and the other with a trunk load of dirty rags; he remembers his father saying he bought both loads in order to say true to the sign’s promise—and then immediately tore down the sign. Harvey says that was his first lesson in integrity.

Soon, they stopped selling used merchandise and focused on new: hardware, electrical, plumbing, paint, and building materials. Identifying and leveraging the quintessential American dream of “home ownership,” Ole’s House of Bargains transitioned to Ole’s Home Centers to become the 16th largest home center chain in the U.S.

Harvey worked in the family business starting at age six, and spent every holiday and summer vacation through high school working, as well as college summers. He earned his Masters of Business Administration degree from Columbia University in New York City and went on to work at the Army and Air Force Exchange Service in Dallas, Texas, before his father threatened to sell the business if he did not come home. His father put him in charge of running the family business at age 25, and Harvey went on to build a solid management team; together, they built the business from four stores to 36 in California and Nevada. In 1984, the business was sold to W. R. Grace and Harvey was given the responsibility of running 90 of its home center stores in the Western U.S.

In 1986, he left W. R. Grace to start KCB Management, a family office and investment company, to manage the family’s assets. Today that business has grown to manage partnerships of real estate and private equity for the Knell family and other high net worth individuals and family offices.

“When I was running our family business, I always said that while the largest asset on our balance sheet is inventory, the asset that really makes the business work is the people”. At Weizmann, he says, people are also the most important ingredient. Institute scientists “discover how things work,” not necessarily for the purpose of creating a product, says Harvey. “Once they discover something, someone else can say, ‘Now we know this. This is the way we can solve this problem’. It’s all about learning.”

Healer at heart

Ellen, a geneticist, was born into a medical family and was a stellar science student as a child. But she also faced barriers—to women, and between scientific disciplines—which, with persistence, she overcame. Both her successes and the challenges she faced have informed her life’s work, her volunteerism and philanthropy, she says, which “are directed at offering opportunities to create better futures for people”.

A specialist in hereditary-risk assessment, Ellen helps individuals and their families assess and understand their genetic predispositions to disease, with a focus on cancer. “You could look at it as science delivering news you didn’t want to hear,” she says. “Or you could look at it as science giving you a window to the future, so you can take advantage of opportunities to mitigate the risk.”

Ellen’s father was born in Germany and received his medical degree in Switzerland in the early 1930s, at a time when German institutions were beginning to close their doors to Jewish students. He had an offer to be a professor of medicine in Germany after he received his medical degree, but he took the advice of his professors in Switzerland and immigrated to America, due to the antisemitism, in 1937. Ellen’s mother, a nurse, met her to be husband while working at a Jewish hospital in Germany and was given the opportunity to immigrate to America when her friend decided to not leave and stay with her boyfriend and offered her exit papers to her Ellen’s mother.

Ellen and her brother spent their early childhood years in Utah before the family settled in California. Eschewing her father’s belief that it was a waste of time and resources for women to seek advanced degrees, she pursued an undergraduate degree at the University of California at Berkeley.

Ellen and Harvey met in high school and married after she graduated from college. They had three boys: Edward, Peter, and Lorin (who passed away in 2023 after a long illness). Ellen then went back to school, earning to PhD in genetics from UCLA. In New York, while Harvey was pursuing his MBA, she worked at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, researching psychiatric genetics, and participating in several studies on twins and dementia.

Upon returning to California, she struggled to find like-minded collaborators; research on the genetics of disease was just in its infancy in the 1970s, and so she found herself devising her own research plan. She worked at the City of Hope in psychiatric genetics and on her PhD, studying the genetics of Tourette Syndrome and its interaction with Attention Deficit Disorder. She also counseled at-risk young adults who had a parent with Huntington’s Disease, a progressive neurological disease with no cure or treatment.

She worked at the Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles in the then-nascent field of familial genetics counseling. She also counseled families whose newborns were found to have a genetic mutation for PKU, a rare, inherited metabolic disorder in which the body cannot metabolize an amino acid called phenylalanine, which is toxic to the brain and nervous system. If the disease is identified early, it can be treated with a strict diet and supplements, and so identification of affected children and counseling are critical. Now all newborns are tested for this disease, among others.

Then, as the genetic basis of various cancers were coming to light, her colleagues encouraged her to begin counseling about cancer genetics. “At first, I didn’t want to do it,” Ellen recalls. “Huntington’s was hard enough. To have to break the news to 20-year-olds that they were at increased risk for cancer was something I just didn’t want to do. But my oncology colleagues convinced me, and they were right—I was able to help people, because if you find out your genetic predisposition and what the genetic mutation does and as well as your likelihood of acquiring the disease, you have control in terms of surveillance and planning. That knowledge is empowering.”

Later in her career, she says she faced her biggest challenge yet in communicating difficult news to patients: the discovery of CDH1. This genetic mutation underlies a rare but lethal form of stomach and breast cancer. “CDH1 is a nightmare,” says Ellen,” but knowing you have the gene before you have the disease is a blessing because you can have life-saving prophylactic surgery,” such as removal of the stomach and/or breasts.

A tradition of leadership and philanthropy

The Knells began their philanthropic journey with a major capital gift to their synagogue, the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center. They were first introduced to the Weizmann Institute by a longtime active Weizmann supporter in southern California, and a dear friend, Lon Morton, and were invited by friends Vera and Dr. John Schwartz of Los Angeles to an American Committee mission to Morocco and Israel. “It was the first time we stepped foot on campus,” recalls Harvey. “We were impressed with the beauty of the campus, and appreciated our conversations with scientists and other guests on the trip. Most were businesspeople who typically ask, ‘What’s the return on investment?’ Ellen and I realized that with basic science, that’s not the criteria. There may not be a product that emerges directly from a specific study, but new knowledge will build on itself and ultimately benefit humanity in untold ways. That, in and of itself, is extremely worthwhile.”

Since those first steps on campus, the Knells have been deeply engaged with the Institute. In 2013, they established a professorial chair for Prof. Samuels, whose research focuses on melanoma. She fuses capabilities in genomics, proteomics, and computational tools in order to identify predictive biomarkers for the disease, and, in turn, appropriate therapeutic strategies.

“I’m extremely grateful for all their support—not only for my professorial chair, but for their long discussions and their friendship,” says Prof. Samuels. “We very much hope that our in-depth understanding of cancer and its mutations will lead to our ability to develop highly personalized treatments that will be relevant to thousands of patients every year.”

“We chose Yardena because she doesn’t follow the conventional path, and it’s not a coincidence, because I never followed the conventional path in my career,” says Ellen. “In melanoma, she could look at the inherited mutations for the disease, but she looks at it from an entirely different angle that integrates expertise from genetics and many other areas.”

Five years later, the Knells established the Knell Center for Microbiology Research, which funds research on microorganisms including viruses and bacteria, which play a role both in human health and environmental health.

During the pandemic, the Knell Center “was instrumental in carrying out research on COVID-19,” says Prof. Sorek. Funds supported the research of Prof. Noam Stern-Ginossar (of the same department), who determined just how the virus overtakes healthy cells, by degrading RNA—a finding that paves the way to the development of new antiviral drugs. The center also supported the investigations of Prof. Ravid Straussman, of the Department of Molecular Cell Biology, who recently discovered how some bacteria contribute to the development of cancer, as well as research from the Sorek lab, which used bacteria as a medium to reveal the inner workings of the immune system.

“Harvey and Ellen really understand how important it is to do basic, interdisciplinary research,” says Prof. Sorek. “Many of the most dramatic discoveries in science originated from the curiosity of a scientist who just wanted to know what happens in nature. They totally get this.”

Just as every sturdy house relies on a solid foundation, the relationship between the Knells and the Weizmann Institute is built on a shared philosophy of the importance of academic freedom and the power of human curiosity. “We love that the scientists are given the freedom to pursue their curiosity—because in the end it may turn out to be very important,” says Harvey. “And we love how the scientists receive everything they need to do their research. We know that all these things don’t happen by themselves, and that those who have the means and grasp the significance of what Weizmann is all about should do everything in their power to support this great institution.”

The Knells’ home in Pasadena, California, built in 1907 and designed by architects Charles Greene and Henry Greene, is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. Called the Robert R. Blacker House, it is built in the arts and crafts style. Its restoration has been a labor of love, particularly for Harvey. The famous 1980s movie Back to the Future and its sequels used the Blacker House as a set (before the Knells purchased it), and the house still receives what their youngest son calls “drive-bys” by ‘Back to the Future’ groupies—and an occasional knock on the door—from passers-by who recall the movie scenes filmed there.

Arts, music, education, community

Beyond Weizmann, both Harvey and Ellen are deeply engaged in a long list of charitable leadership roles across a range of areas.

Harvey is past president of the National Hardware and Home Center Council for the City of Hope Medical Center. In the Jewish community sphere, he was the first General Campaign Chair of the San Gabriel and Pomona Valleys Jewish Federation and was president of the B’nai B’rith Youth Organization Trust Board.

In the arts and music, Harvey is a past president and longtime member of the board of the Armory Center for the Arts—which, among other activities, teaches artists to work as teachers in elementary schools—and is a past president of the board of the Pasadena POPS Orchestra. A lifelong music lover, he is also the organizer and a founding member of MUSE/IQUE, an orchestra and unique performance organization—which he calls his “best start-up”.

Ellen sits on the Board of the Cancer Support Community in Pasadena, to which they recently gave a major gift, which provides non-medical support services like counseling, group sessions, education, art and yoga at no charge to the recipients. She is active in Professional Child Development Associates (PCDA), a nonprofit organization that provides services for children with autism spectrum disorder. She is also past president of Southwest Chamber Music, an ensemble that won two Grammy Awards while she was President. Ellen also served on the boards of Mothers’ Club, helping families escape poverty through preparation for school; the Beit Issie Shapiro board for children with multiple handicaps, located in Israel. She was an active board member for the local Jewish federation and was vice president of finance for her synagogue for many years.